This year I have felt a positive shift in my relationship to meditation practice, going from something I do because it’s good for me to something I want to do. This guide is an attempt to document how I’m currently thinking about meditation in the hopes that it will help me remember what I have learned and maybe also help inspire someone else1.

I have been either meditating daily (30% of the time) or feeling bad about not meditating daily (70%) for about nine years, which is not very long among True Meditators but feels long to me. A lot of that time felt like I was banging my head against a wall, though maybe that was all necessary given where I was at in life. I’m very grateful to my more experienced friends who shared what they knew and gave me inspiration, to the teachers who wrote helpful instructions2, and to myself for never giving up entirely – at least not yet!

To be clear, this is my guide to meditation, tailored to how I work3. I hope it might be helpful to the extent you and I are similar.

An overview

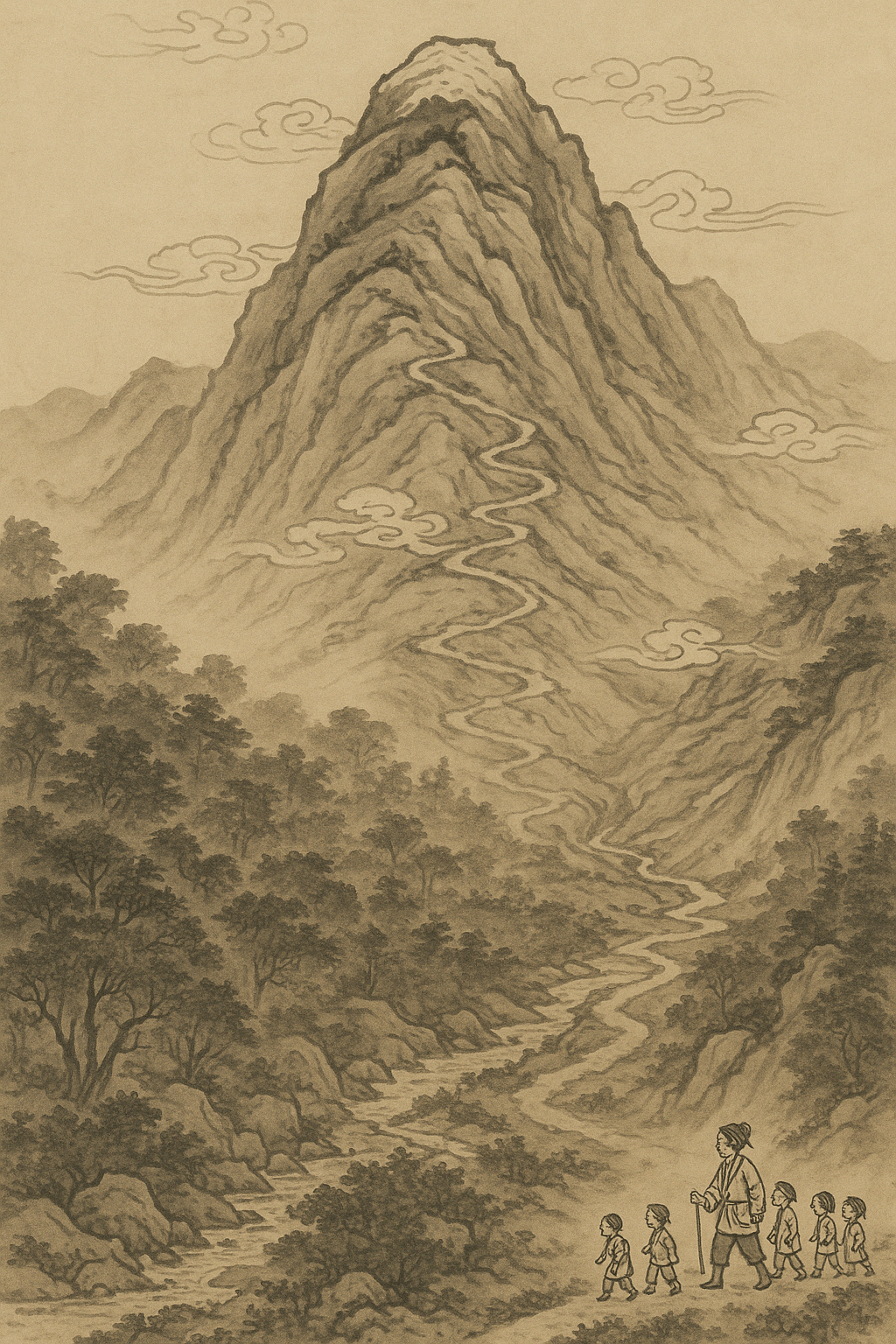

First, I define the basic terms of the analogy – the kids and the mountain. The rest of the piece is structured following the hiking analogy; I start with preparations before you leave home (a procedure to follow at the start of meditation). The core of the piece is guidance on hiking up from the base of the mountain (starting to meditate and dealing with the different things that can come up). That is followed by a smaller section on the higher parts of the mountain (different meditation practices to try when your attention is more stable). I then conclude with a very brief section on coming back down (a couple of things to do at the end of the meditation session).

Introducing the analogy

It can be useful and fun to think about meditating as if it were leading a small group of children to hike up a mountain.

The kids

You and the kids are different parts of your mind. “You” are the (sometimes) more self-conscious and deliberate part. The kids are the other parts of your mind, whom you are trying to convince to meditate.

I like to think of some of these parts as kids and some as pets because, in my experience, some of them behave like older children (they understand more complicated concepts) and some more like very young children or animals (they’re more in the stimulus/response world of primal drives). Since I live with two cats and like them very much, I like to think of that latter group as cats rather than children, but I use “kids” throughout for simplicity.

The mountain

The mountain is your experience of your mind as you meditate. You start at the ground-level of experience, which is similar to your day-to-day life. You ascend the mountain as you progressively become more and more concentrated. Places that are very high up in the mountain (highly concentrated states) provide you with unique views of the surrounding land (insights about experience, life, etc.).

In this mountain there is a single trail that gets you about halfway up (representing the different methods to stabilize your attention from its usual, flittering state), which I call the access trail. At the end of that trail, there is a crossroads, with many different paths leading up the mountain (the different,more advanced techniques).

Like many mountains, this one has more diverse features – lots of trees, creeks, plants, and wildlife – at the bottom and gets more and more barren as you ascend. This is meant to convey that you are more likely to get distracted from the meditation object at the early stages.

Which meditation?

I came to meditation through Buddhism, and so will be referencing a few classic techniques from this tradition:

- Mindfulness of the breath (anapanasati)

- Walking meditation

- See/Hear/Feel (not a Buddhist meditation but derived from one)

- Lovingkindness (metta)

- Tonglen

- Jhana practice

- Insight practice

I think the analogy might be helpful for other types of contemplative practice but that’s only a guess.

When I refer to “the meditation object”, I just mean whatever it is that you’re concentrating on in your chosen type of meditation. The classic choice of a meditation object is the sensations of the breath, but there are a lot of different options.

I don’t give specific instructions on how to perform any of the above techniques; those are readily available from the much more accomplished authors linked above.

Notation

In the following sections, I’ll describe the literal meditation instructions in italics first.

Then I’ll draw out the analogy for those instructions in regular font.

Before you leave home

If you’ve ever been on a hike and realized you forgot snacks or water halfway through, you know that the project of the hike really starts with a little planning at home.

Why are you going?

As with most difficult endeavours, it is a good idea to consider why you are meditating in the first place. For me, there are four reasons to bring the kids up the mountain:

- It’s good exercise. Meditation strengthens your concentration and background awareness, which are generally useful skills in life. It can often have calming effects and improve your mood as well.

- Forest-bathing is healing. Some of the techniques here will surface difficult emotions and memories that could benefit from your attention. Meditation can often be a helpful way to process these emotions and heal some of these psychic wounds.

- It’s good team-building. Getting the different parts of you to all work towards the same goal is a very useful skill in life.

- The views are great (if you make it there!). The stillness and concentration involved in meditative states often lead to important insights about yourself, your life, and the world. You shouldn’t expect there to always be insights, however, and it is a good idea to not expect any on any particular meditation session4.

The essential, underlying reason for taking the kids up the mountain is that you love them and you think it will be good for them. You are not forcing them to come with you, you are persuading them.

Check in: How are the kids doing today?

You’ve assumed your preferred position for meditating and you’ve checked your posture. Now you run a quick body scan to check if you are holding tension somewhere, if something (temperature, the room you’re in) needs adjusting, your energy level, and whether you can notice any emotion5. You label what you find to yourself without trying to get caught up in the story of why you feel that way.

Every member of the crew agreed to come to the hike at some point, in some way – that’s why you’re about to meditate. Things might have changed since they agreed, however. You should also remember that some of the kids are too young to notice if they’re too tired or hurt to go on a hike and too young to tell you these things unprompted.

So, it is a good idea to check in with the kids for a minute or two: “How’s it going today? Anything on your mind?”. Often the answers will be pretty dull; that’s fine, the check-in is to catch the times when the answers are not dull. Give each kid a look-over to confirm what they’re telling you before you make them get in the car and schlep it all the way to the mountain.

Choosing to meditate: Are we really doing this?

You have surveyed your current state and you briefly consider whether it is a good idea to meditate right now or whether it would be more helpful to do something else.

Once you’ve checked in with the crew, it’s time to make a go/no-go decision. I have found that there are ways to deal with most physical and emotional issues in meditation to great benefit, but that’s only up to a point – please don’t force the kids to go on a death march out of some sense of “suffering builds character”.

You might talk a groggy kid into doing the hike because you know he’ll wake up as he walks, but I hope you wouldn’t force a kid who didn’t sleep at all or who has a sprained ankle to go up a mountain! Maybe everyone is too tired to hike and you all should try to take a nap / NSDR instead. Maybe you should go have a snack – surprise those poor kids by taking them to get ice cream instead!6

Having a plan: Where are we going, again?

You’ve decided it makes sense to meditate, and you are keeping in mind the things you noticed about your current state in your earlier scan. You quickly sketch out a plan, for example – “I’m going to meditate on the breath until I don’t need to count anymore. Then I’m going to keep meditating on the breath until it feels really stable, and then I’m going to do some jhana practice. I’m feeling pretty blue about my friend’s situation today, so if that starts to come up I will focus on that and do tonglen practice until I’m ready to go back to the breath.

Let’s say that this is a good day to go up the mountain. You don’t really need to know which place you want to go before you reach the end of that first trail, but why waste precious hiking time? Better to have a sketch of where you want to go if things go as planned (while knowing they might not!). This will be your default plan in case nothing more appealing comes up.

Get pumped: Grounding in your intentions

You take three long, calming breaths and try to relax. In your mind, you ask yourself why you are meditating today and answer that you hope it can help you be a little kinder to yourself and others today. You say that you are grateful for the coffee you just had, for the sunny Spring day, for your friends, and try to feel that gratitude as you do. Finally, you spend a minute or two in metta practice.

You’ve confirmed that the crew is ready and willing to go and you have a gameplan for when you get there, so you can now get in the car and head out to the trailhead. While driving though, why not chat to the crew and get them psyched for the big adventure? It is worth spending a minute or two on setting a helpful attitude for everyone.

Run through these exercises7 in your head explicitly so that all your different parts can hear:

- Remember, kids: we all voted to go hiking. Are you meditating because it is supposed to be good for you? Because it will calm you down? Because it is connected to some broader goal? Re-articulate the reason every time to make it feel emotionally honest – no parroting words that used to be true!

- Isn’t it cool that we get to go hiking? Mention two or three (or seven!) things you can feel genuinely grateful for in that moment. They don’t have to be big or “spiritual”; I’m often grateful for breakfast or coffee.

- I’m so lucky to get to hike with you guys. I wish more of our friends could be having a good time, too. Do a minute of metta practice. Never miss yourself! If there are parts of you that are struggling, direct lovingkindness directly to them (e.g. “may my broken heart be happy / well / free from suffering”).

Maybe the equivalent of this is asking the kids to each share why they’re excited to go on the hike. Maybe it is like getting everyone to sing a funny song about going to the mountain. Whatever the analogy is, you’re just trying to get everybody feeling good and motivated before you get going.

On days that feel bleak, it can be tempting to skip this part; the kids are all half asleep or cranky and it feels insulting to get them pumped up. I think it’s still worthwhile to do it – if it feels impossible, maybe that’s a sign that you should do something other than meditating!

On the access trail: Beginning to meditate

Getting going

You are now trying to keep your concentration on the meditation object, in this case your breath. You start by counting the breaths to help you stabilize your attention.

On an exceptionally good day, all the kids might be stoked to go up the mountain and will just march happily behind you. Notice the heavy lifting being done by the word “exceptionally”.

Because you are a savvy guide, you came prepared for this: you brought along a little bit of rope, and you asked everyone to hold onto it as they walk behind you. Of course, this is only a partial solution: a very restless kid will just drop the rope to go look at some cool thing somewhere along the path! If many of the kids let go of the rope, it will become easier for you to notice that something has gone wrong, but you still have to notice.

Similar tools are available in some kinds of meditation. For example, with mindfulness of the breath, you can count your breaths in your mind to help you keep focus. Just as with the rope, the counting only helps in noticing whether you’ve lost your focus; you have to be paying enough attention to the counting to actually notice.

Handling distractions: Someone’s gone missing!

You are counting your breaths (or labeling, or any other handrail tool) to try to keep focused on the meditation object and you are dealing with distracting thoughts, emotions, and sensations. Whenever you get distracted, you gently bring your attention back to the breath / meditation object and start the count again.

You are trudging up the access trail with the kids behind you. It is very likely that at least one of them will repeatedly wander off to look at a cool bug or a flower or have an issue and you will have to stop the group and go bring the wandering kid back into formation. But of course, while you’re grabbing the first kid, some other kid might get bored and wander off in a different direction. You might come back and find no one else waiting for you!8

This is a test of patience and compassion for you as the children’s guide. If you get annoyed and bring that irritated, complaining attitude to the situation, some of the kids might respond. Others will bristle and run away even more if you choose that approach, however. Irritated, judgmental nagging is not the ideal strategy to convince any of them.

If you are like me, your irritation is most likely coming from the sense that “this isn’t actually hiking, I’m just corralling children, we’ve barely left the trailhead, we’re not going up the mountain”. Try with all your might to see that you are in fact already hiking in the mountain and achieving most of your desired goals. Rounding up the kids will be much more fun if you (the conscious part of you that is trying to focus on the meditation object) are calm while you do it. That calmness will come from accepting that this is just where you and the kids are at today, and that there is nothing wrong with that. This is much, much easier said than done, of course.

Investigating persistent distractions: Use your words

You’ve been meditating for a while and have mostly spent your time getting distracted, noticing that you’ve lost track of your meditation object, and bringing your attention back. You’re not even able to count to ten breaths9 without getting distracted! You decide to temporarily stop trying to meditate to try and find strong emotions or sensations in your body that might be causing distraction. You start with the things you noticed during your check-in; since you were feeling blue about your friend, you try to identify the feeling of sadness in your body and focus your attention on it10. Once you’re locked on to the sensation, you try a few different labels for what’s going on (“I’m feeling sad about my friend’s situation”; “My friend’s situation reminds me of something that happened to me”) until the sensation responds (usually by intensifying) and confirms your guess. You try to avoid getting sucked into the story behind the label by focusing on the sensations.

After the fourth – or eleventh – time you’ve had to stop the group to go looking for a missing kid, it dawns on you that it has consistently been the same kid who’s wandered off. Instead of just silently grabbing their hand and bringing them back as before, this time you crouch down next to them and try to gently inquire what’s going on. It helps to do this in a loving, patient way; it’s not helpful to blame the kid for wandering – they really can’t help it! It will be much more productive to swallow your impatience and try to help them troubleshoot.

Remember that the child isn’t old enough to simply explain what’s going on. Based on your earlier check-in, you might have some clues as to where to start the questions. At this point you’re looking for just a yes/no answer to your questions: Are they tired or too cold/too hot? Are they very sad or angry or worried about something? Do they have a pebble in their shoe?

Once the kid confirms one of your guesses about what’s going on, then you can explore that path further and ask if it’s about X or Y thing. Often, once you guess right about why they’re feeling what they’re feeling, they’ll start crying and trying to tell you the whole story of why they’re feeling the way they’re feeling. Instead of starting a lengthy conversation with the kid, you tell them you’re going to try and help them deal with what’s going on right now and that you can talk about the whole story of what happened once you’re both off the mountain.

Working with difficulties: Applying first aid

You’ve figured out why you’re experiencing this strong emotion or sensation that is distracting you from the meditation object.

Like any good guide, you know a little bit of first aid and you brought your kit. After diagnosing the issue ailing the child, you bring out the correct tool in your kit to deal with it:

- Difficult emotions: You’re going to hug this kid and tell them that you’re sorry they are having a hard time, and you’re going to do it until the kid says they’re ok to keep going.

- You are sad because of your friend’s pain. You begin tonglen practice to visualize and take in that pain with the in-breath and then send out acceptance and healing with the out-breath.

- OR: You are sad because your friend’s situation reminds you of a painful memory. Based on what you found, you begin metta practice, sending loving intentions to your bruised heart first, then to your friend’s, and then to all people dealing with heartache.

- You keep going until your time for meditating is up or, if the sensations quiet down (and maybe you begin to lose focus on them) you decide to go back to observing your breath.

- Unpleasant sensations: If the kid has a pebble in their shoe, remove it! If the kid is tired or sore but still wants to go on, help them see that they are not seriously hurt and that it’s no big deal to keep going. You do this until the kid confirms they are good to go.

- You determine that it is back pain that is distracting you. You immediately make a physical adjustment (e.g. changing your posture, readjusting your cushions, etc.) and pay attention to the effect.

- If you tried the adjustment before or you suspect it won’t do any good, you decide to make your pain or discomfort the object of your meditation11 until you feel it is a good time to tackle any accompanying suffering (see below), go back to your previous meditation object, or keep focusing on the sensations until the end of your meditation.

- Suffering: Sometimes it is possible to see that the reason why the child is tired or in pain is because they are carrying a big rock or a branch of poison oak in their hands. You might try to show the child that those things are causing their distress and persuade them to drop the harmful object. You keep at it until the kid says they are good to go back on the trail.

- After spending time attending to your difficult emotions and unpleasant sensations, you notice that you are also experiencing negative emotions about those primary emotions/sensations; you recognize these secondary emotions as suffering.

- You then ask yourself: what is the belief behind this suffering? What is the belief about the person that is experiencing the suffering? Once you identify these beliefs and contemplate whether they are accurate and helpful, you visualize any unhelpful beliefs as a weed that you cut down and then uproot.

- Once you’ve done this, you observe your body for any sensations of strength or freedom resulting from the exercise as positive feedback for the work you’ve just done 12.

- Once this is done, you go back to focusing on your emotions/sensations if you feel you still need to, or you go back to your original meditation object.

When things get overwhelming: time to go home?

Focusing on the difficult emotions makes them swell up uncontrollably; you begin weeping and sobbing as painful memories and images come to mind. You try to retain some separation from these powerful emotions but it is very difficult.

You resort to reciting your words for metta practice: “may I be happy, may I be well, may I be free from suffering”, and you continue sending yourself lovingkindness while you weep. Eventually your timer bell rings and you take some deep, calming breaths. You consider what might be helpful for you in the rest of your day.

OR: you keep reciting the words of metta practice but they feel hollow. Eventually you give up and lie down to give yourself fully to crying. After you’ve calmed down and rested, you decide to make an appointment with your therapist and you text a trusted friend for some comfort in the meantime. You’re probably going to eat a whole pizza for dinner tonight.

It could be that the kid is injured and you just need to get off the mountain right away – please do so if this is the case. Most times, however, the kid just needs some loving attention. You’re already in the ideal place to provide that attention – a beautiful, quiet space that is entirely for the benefit of the kid – so why leave the mountain early?

Hitting your stride: Reaching stable attention

You’ve dealt with the emotions, sensations, and stories that were distracting you and have gone back to attention on your breath. You’ve stabilized your attention on the meditation object enough to let go of counting or any other supportive tools. Some thoughts appear in the background every now and then but you are able to notice them and not get hooked. Your breath is very shallow and you feel quite still.

The conditions were right for the kids to walk in formation and eventually you took back your rope. You are now moving as a unit and covering good ground. You’ll be at the crossroads in no time!

Ascending the heights: A sketch of more “advanced” practices

You’ve reached a stable and continuous attention—what’s sometimes called access concentration or just the start of it13. You remember the plan you set out at the beginning of the sit and you begin practicing the technique you planned.

You get to the crossroads and follow your gameplan, hoping to catch some beautiful sights.

This section is very short because I have a lot less experience with this part of the mountain!

Two trails towards the heights: Deepening concentration

So far, I have been up two of th etrails that lead up to the top of the mountain (and just the beginning of them!):

- Keep going straight (mindfulness of the breath, body-scanning, see/hear/feel, etc.).At the crossroads, keep going in the same direction all the way to the peak. You can just keep doing the same kind of meditation that got you to access meditation and keep going deeper. The Mind Illuminated covers the details of how to hike in these high altitudes in great detail by practicing mindfulness of the breath, for instance.

- The tunnels (jhana practice). Jhana practice is like going inside the mountain through a series of tunnels that lead to the same spots as the straight and narrow road described above. The first jhanas are like tunnels covered in precious stones, then dimmer crystals, and then smooth obsidian; they are so different from the mountain and are pleasantly cool after the long hike, so the kids love them. I have heard that the other tunnels leading up the mountain go entirely dark and can sometimes feel spooky if you don’t know the way, but I couldn’t tell you myself.

Looking out: Contemplation and Insight

At this altitude in the mountain there are many spots where the foliage opens up and you can show the kids some beautiful views. From there you can see the town where you all live, the different places where you go and hang out, the people moving about like little ants. Looking at things from such a different perspective can really teach the crew lasting things about their world; it’s a wonderful payoff to all that hard work you’ve been doing together.

For me, it’s helpful to both appreciate the opportunity to get up to these parts of the mountain while reminding myself that it’s no big deal – it is the effort to climb the mountain that is truly worthwhile.

Some insight practices involve observing experience in extremely fine detail—such as tracking impermanence in bodily sensations—while others begin with contemplative reflection, especially in early stages. More advanced insight is usually non-discursive14.

The contemplative reflection practices – the ones I’m most familiar with – can involve contemplating your life and stories you tell yourself while in a highly concentrated state. That state makes it more likely that what you learn from the practice isn’t just intellectual, but a more holistic understanding; like the difference between knowing that smoking is bad for you because you read about it and having the desire for smoking cease because you get it is bad for you.

Going back down: Wrapping up your session

Your meditation timer bell rings and you decide it’s time to stop. You briefly review what happened during the session – you had a hard time getting concentrated, you focused on the sadness you were feeling and practiced metta, eventually you went back to the breath, got stable enough to some jhana or insight practice, and then the bell rang. You make a note of your still-heavy heart and plan to take it as easy as you can today to give yourself some space to heal. You wrap up by thanking yourself for meditating and by wishing that whatever good the meditation did you can be expressed through your actions in the world.

You run out of time and now it is time to quickly get back down the mountain. Fortunately, there is a conveniently placed gondola15 that you can just pile into and ride back down. While you’re riding, take a minute to go over the hike up and see if there’s any lessons you can all learn for next time.

Once you’ve done that, all the hard work of guiding is over – thank the kids for being good sports and praise them for how strong they’re getting – they’ll be that much better at sports or whatever it is kids like doing these days. If the kids are a little beat up from the hike up, remind them to take it easy on themselves for the rest of the day. After all, you’re all coming back to the mountain tomorrow!

- Writing this also has the added benefit of allowing me to hold forth about this topic I’m excited about and letting the people in my life opt in instead of being forcefully subjected to the experience. ↩︎

- My main guides, in chronological order, have been: The Miracle of Mindfulness, When Things Fall Apart, The Mind Illuminated, The Science of Enlightenment and the online writings of Shinzen Young, Right Concentration, and Seeing that Frees. Also: a big shout out to the OG! I found these more helpful than in-person talks at Buddhist centres and Youtube videos / podcasts but those were good too! ↩︎

- My usual challenges are: a relatively high baseline anxiety, an overactive mind with a love for stories, overpowering feelings (sadness, fear, hopelessness, helplessness are common ones), impatience, etc. I generally put too much pressure on myself when trying to do things and have difficulty relaxing. I don’t usually struggle with boredom or sleepiness (what the Buddhists call sloth/torpor). ↩︎

- I have found the analogy of going to the gym helpful: It is OK to have ambitious fitness goals and to plan your gym sessions accordingly. Once you’re in the gym working out, however, it is a waste of time and energy to be constantly checking yourself in the mirror to see if you’ve got abs or huge biceps yet. It’s better to focus on working out with the correct form and to pay attention to your body so you can make adjustments to your workout plan if need be. Trust the process, etc. ↩︎

- I check the throat and chest, which are common seats of emotional sensations, but you may be different. ↩︎

- If you are generally a person that tries really hard, and often too hard, this is probably the right approach. If you struggle more with sleepiness and lack of motivation, you might want to take a different approach (e.g. going through your intention for meditating in more detail, etc.). ↩︎

- These cues come from Leigh Blasington’s excellent Right Concentration, though different manuals will recommend many of the same things. ↩︎

- It is possible to be distracted by multiple concurrent things, I have found to my dismay. ↩︎

- Or eight! Brasington recommends eight because it is harder to go into full-auto counting mode than with ten, and it works for me. ↩︎

- I find it helpful to keep part of my attention on my breath as an anchor while I examine the sensation, especially if I’m feeling very agitated or sleepy. Otherwise, it is easy to get distracted from the investigation itself! ↩︎

- It is not always straightforward to figure out whether you should physically change anything to deal with pain or discomfort . If you are a try-hard, then I would say err on the side of mindfully making the adjustments without any further fuss (with apologies to the venerable S.N. Goenka!). Sometimes, especially if making the above adjustments didn’t make a difference, meditating on the discomfort / pain can yield very interesting results. ↩︎

- These exercises are referenced in Chapters 3 and 10 (and probably others) of Rob Burbea’s excellent Seeing that Frees. With metta and tonglen practice, you don’t need to distinguish between the primary emotion/sensation and the suffering – you’re showing compassion and lovingkindness for both. However, investigating the beliefs at the root of your suffering while vividly experiencing that suffering can be an excellent opportunity to weaken that loop. ↩︎

- How concentrated you need to be to qualify as being in “access concentration” is apparently a matter of great debate. Personally, I’m for the view that you can try out insight, emptiness, and jhana practices before getting complete one-pointedness in your concentration. Sure, you’re not going to get everything you could possibly get out of those practices, but you will still get quite a lot! Additionally, even an imperfect jhana practice can help you continue honing your concentration. ↩︎

- In the Buddhist tradition, you are looking for direct insight into the “three marks of existence”: impermanence, suffering, and no-self. Achieving that direct insight in a reliable, repeatable manner is often called “Stream Entry” and is the first of four steps towards full, capital E Enlightenment. You’ll have to take the Buddhists’ word for it as this stuff is way above my level. ↩︎

- We could extend this part of the analogy by saying that taking certain kinds of psychedelics with certain kinds of set and setting is equivalent to taking the gondola up the mountain. There is a price to that ticket (you might be wiped for a while after), the gondola is not 100% safe (you might have a bad trip) or reliable (sometimes you just see pretty colours), and you are not building the muscle to reliably get yourself up there nor around in your daily life. All of this is supposition based on hearsay, mind you. ↩︎

Leave a comment